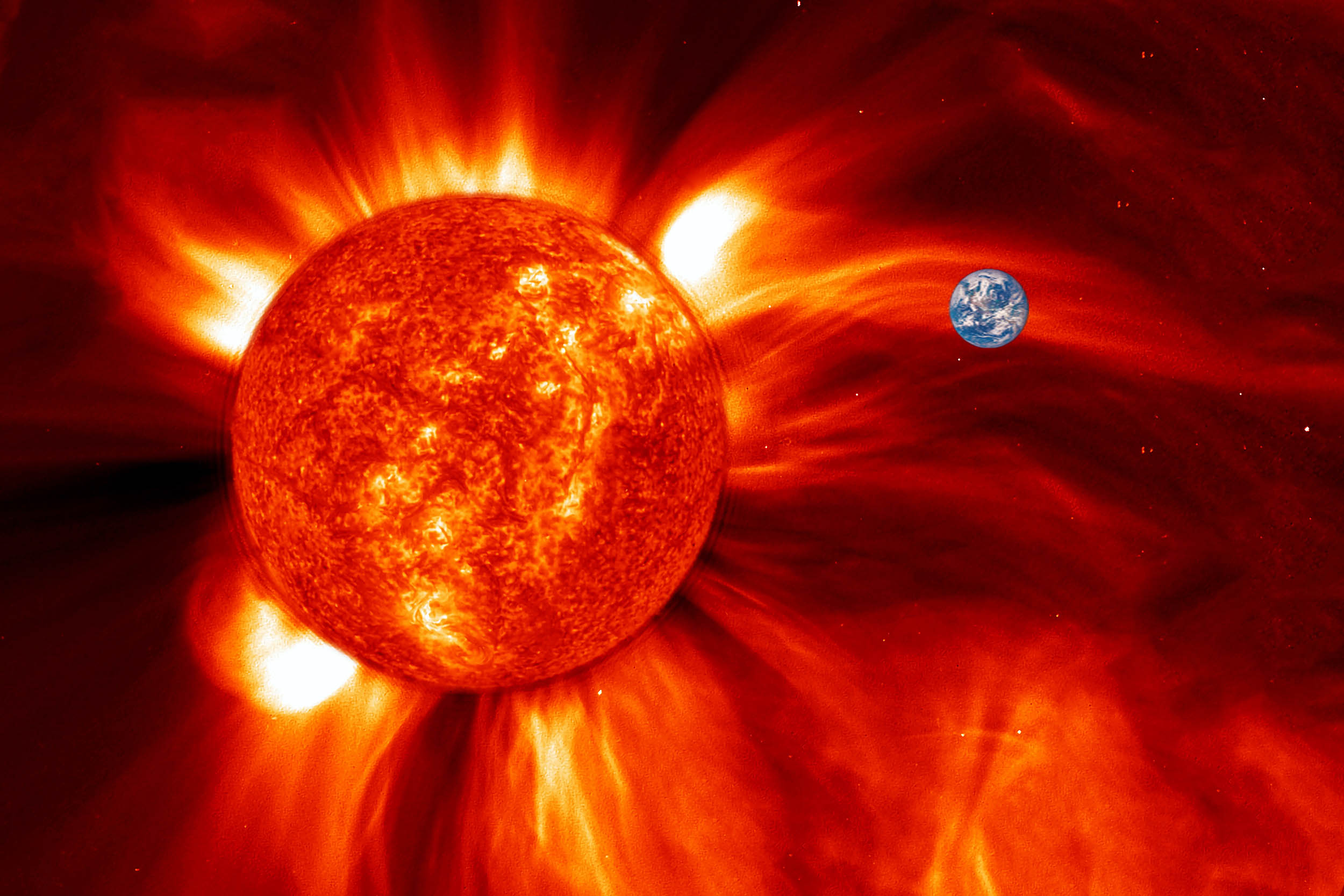

On January 6 a powerful solar flare erupted from the surface of the sun. It was the first X-class flare—the strongest type on the flare intensity scale—in around two months. Two further X-class flares followed within the next few days, marking a distinct uptick in solar activity—and in breathless speculations that the flurry of flares could threaten us here on Earth. One U.K. tabloid raised the possibility of “major continent-wide power blackouts.” “Terrifying solar storm coming to Earth,” read another outlet’s headline. Heliophysicists and other scientists studying “space weather” warn that flares and related solar outbursts can indeed interfere with modern life by damaging power grids, as well as by increasing radiation exposures for occupants of space habitats and high-altitude aircraft. But even so, such experts say, the risk of harm arising from inclement space weather remains far lower than many media reports often suggest. Does that mean we shouldn’t worry any time our star decides to belch in our general direction? Not exactly. Knowing what to worry about and when, however, requires proper context and perspective. Solar flares arise within the sun’s roiling soup of plasma when charged particles thrash around one another to form intense magnetic field lines that can tangle and interweave. When these magnetic fields suddenly shift or realign—as often happens in sunspot-pocked “active regions” of the solar surface—an enormous amount of energy is released. There is no question that these solar eruptions, and particularly X-class flares, are mind-bogglingly powerful. One of the strongest solar flares ever seen, the Carrington Event of 1859, may have released as much energy as 10 billion megatons of exploding TNT. Imagine the infamous Tsar Bomba—the most powerful thermonuclear weapon ever detonated—and you’re about five billionths of the way there. Most solar eruptions are nowhere near this energetic. But they can still propel enormous, planet-engulfing clouds of plasma called coronal mass ejections (CMEs) toward Earth, as well as anywhere else in the solar system. Direct hits on our world by CMEs can and do occur, and each event packs more than enough oomph to discernibly disrupt some modern electronics. Even so, such disruptions are usually subtle and have little to no impact on most peoples’ daily lives. another page In aggregate, spates of space-weather scaremongering are easy to predict because they’re usually tied to solar activity itself, which follows a roughly 11-year cycle. Each round of the cycle sees our star oscillate once between two main states: the solar minimum, in which flare activity tends to be at its lowest, and the solar maximum, in which flare activity tends to be strongest. Currently, the sun is slightly more than two years away from its maximum, so heightened activity (and media alertness) is to be expected now and for the next few years a coronal mass ejection (CME) is a significant ejection of magnetic field and accompanying plasma mass from the Sun's corona into the heliosphere. CMEs are often associated with solar flares and other forms of solar activity, but a broadly accepted theoretical understanding of these relationships has not been established. If a CME enters interplanetary space, it is referred to as an interplanetary coronal mass ejection (ICME). ICMEs are capable of reaching and colliding with Earth's magnetosphere, where they can cause geomagnetic storms, aurorae, and in rare cases damage to electrical power grids. The largest recorded geomagnetic perturbation, resulting presumably from a CME, was the solar storm of 1859. Also known as the Carrington Event, it disabled parts of the newly created United States telegraph network, starting fires and shocking some telegraph operators. Near solar maxima, the Sun produces about three CMEs every day, whereas near solar minima, there is about one CME every five days In short BIG BAD SACRY HIDE RUN BIG BAD NOT GOOD THIS IS NOT FEARMONGERING. Linky

Will the real Linky please stand up?

Will the real Linky please stand up?